Moral Injury as the Root of PTSD: Ukrainian Context

Is there a pain deeper than fear? Is it possible to sustain psychological trauma without facing a direct threat to life? And can a person destroy themselves – not because of what was done to them, but because of what they did or failed to do, in violation of their own values?

These are the questions answered by Dr. William P. Nash – a military psychiatrist, clinician, and researcher. A specialist with over 40 years of experience working with veterans, U.S. Marines, physicians who endured the “hell” of the COVID-19 pandemic, and others whose minds were fractured not only by pain, but by moral rupture.

On Friday, May 23, 2025, he delivered a powerful lecture at the III International Scientific and Practical “Well-Being Leadership Conference” held in Lviv under the auspices of the Center for Leadership of UCU, UCU Business School, the Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership at Ivey Business School, and the Institute of Mental Health at UCU. A lecture that can profoundly reshape our understanding of stress, PTSD, responsibility, and – most importantly – the very meaning of Leadership in times of crisis.

The team of the Center has gathered for you the speaker’s key insights – those that can become a lens for understanding our own inner transformations. And beyond that, for grasping the immense path to healing that awaits not only individuals, but an entire nation.

What Is Moral Injury and How Does It Manifest?

Moral injury – a term that only entered the psychiatric lexicon in the 2000s – is, according to Dr. William P. Nash, what a significant number of soldiers, medics, leaders, volunteers, and civilians experience during times of crisis.

“Moral injury is the lasting harm that results when a person or community experiences a betrayal of moral trust – either their own or someone else’s – in a high-stakes situation”,

explains the researcher.

It’s not always about “great evil”. Moral injury may stem from:

- being helplessly present in a situation of injustice;

- participating in actions that violate one’s core values;

- the feeling that “I betrayed myself”, or “I was betrayed by those I trusted”.

The term “moral injury” was first used by psychiatrist Jonathan Shay in his 1994 book “Achilles in Vietnam”, where he compared the experience of Vietnam veterans to ancient heroes. He convincingly argued:

“People can recover from horror and loss – as long as what is right has not been broken”.

PTSD, Fear, and Moral Betrayal: What Truly Breaks the Psyche?

“In 40 years of practice, I have never seen a single case of severe PTSD caused by fear alone. Only by moral injury”,

emphasizes Dr. William P. Nash.

This statement is supported by a large longitudinal study led by him in collaboration with the United States Marine Corps. Over the course of a year, the research team observed more than 3,000 Marines before, during, and after combat deployment. They collected over 1,000 variables – psychological, biological, behavioral, and familial.

The results were striking:

- Childhood trauma explained only 1% of new PTSD cases.

- Combat exposure accounted for just 3%.

- But morally injurious events and dissociation during stress explained over 20%!

The strongest predictor was what the researchers termed “peritraumatic dissociation” – a state in which a person, in the midst of a critical situation, seems to “shut down”, becomes paralyzed, or fails to act when they were supposed to. If this leads to harm to others, it often results in a profound sense of guilt – and ultimately, moral injury.

“Not the combat itself, not the external enemy, but the internal feeling of betraying one’s own values – that’s what leaves people deeply wounded”,

the speaker notes.

How Does a Person Heal – and What Role Do Leaders Play?

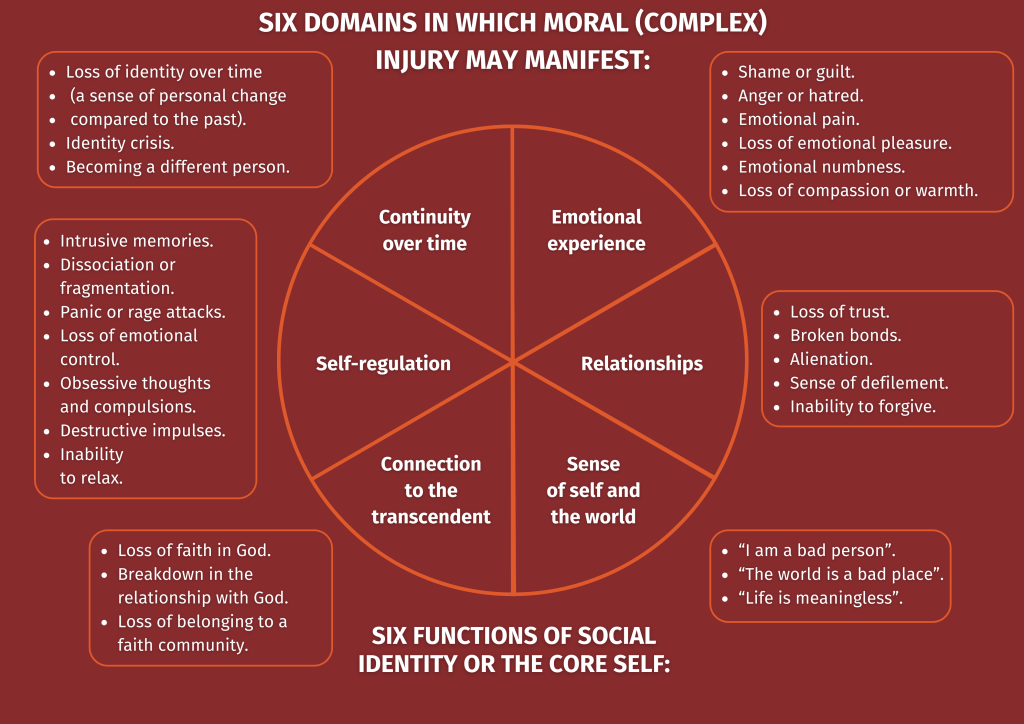

Moral injury is not reducible to symptoms – it strikes at the core of what makes us human. Dr. William P. Nash identifies six domains of injury he has observed in his patients from Iraq, Afghanistan, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, and the civilian healthcare system:

- Emotions: guilt, shame, loss of the ability to feel.

- Relationships: isolation, family breakdown.

- Self and worldview: loss of trust in oneself and in the meaning of life.

- Spirituality: disconnection from faith.

- Physiology: bodily responses such as panic, insomnia, addiction.

- Identity: rupture between the past self and the present.

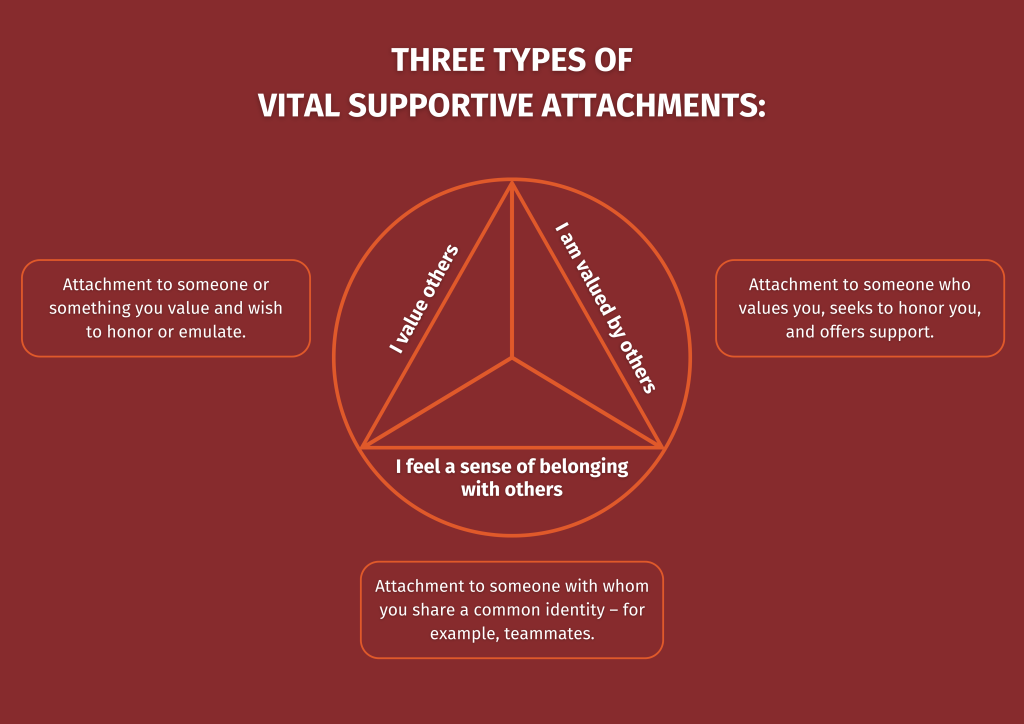

In response to this multidimensional trauma, specialist proposes the metaphor of a “moral engine”. This approach is based on the work of Austrian-American psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut, who identified that human life is sustained through three types of attachment:

- to those we value;

- to those who value us;

- to those with whom we identify.

When one of these attachments is lost, a part of the self disappears with it. That is why the Doctor applies a practice called “moral mapping” – a process of identifying which attachments have been broken, and which ones can be repaired.

Five Steps Toward Healing

- Become a temporary source of value

“I know what happened. But you are still worthy of love”,

explains the researcher, describing the key principle of this stage. - Stabilize the physiology

Through caring for the body, restoring sleep, and creating safety. - Make amends for the harm done – even symbolically

“You can’t put a shattered bell back together. But you can still make it ring”,

the speaker said, metaphorically. - Restore attachments

Through new experiences, pets, community, and service. - Leadership as a resource – or a threat

“Institutions do not have a conscience. So the leader must be the conscience”,

concluded Dr. William P. Nash.

For Ukraine, This Is Not an Abstraction – It Is Our Reality

A society at war, bearing immense responsibility and devastating losses, is experiencing mass moral injury. Soldiers, doctors, volunteers, families of the fallen – all carry a pain that exceeds the boundaries of clinical psychiatry.

“When someone in crisis comes to you – don’t ask, “What’s wrong with you?” Ask,“What happened to you?”…”

advises the psychiatrist.

This is the core message of the international guest speaker. And it is a challenge – not only for therapists, but for leaders who must either offer new connections, or leave a person alone in silence. And our readiness to meet that challenge matters now more than ever.